Wang Yu: Distinguished Physician of Qing Dynasty Shanxi

(I) Early Life

Wang Yu (1822-1862), Sex: Male, styled Rongtang and known by the literary name Runyuan, was born on December 27, 1822, into a scholarly family in Hantun Village, Jiexiu County, Shanxi Province. He began studying at a private school at age seven under tutor Pang Yunpu. A diligent learner, he practiced calligraphy until his papers turned black with ink and even used brooms to write large characters on the ground. Later, he studied Confucian classics, history, and Neo-Confucianism under Qi Shen’an, composing poetry and essays with such intense focus that he often bit his fingers raw and ground down his teeth while contemplating.

To prepare for imperial exams, he authored hundreds of poems using vocabulary from the Wujing (Five Classics) and Wenxuan (Literary Selections). Between 1841-1842, his mother’s illness spurred him to self-study medicine, and he gradually began treating patients. In 1848, he earned the xiucai (county-level scholar) title, and in 1850, he attained the prestigious bagong (senior licentiate) rank, entering the imperial court as a Secretary in the Grand Secretariat, where he managed documents and co-compiled the Fanglue (Strategic Regulations).

(II) Official Career and Medical Practice

During his 1856 posting to Shaanxi, he adjudicated legal cases with such fairness in overturning wrongful convictions that locals hailed him as the “Divine Judge.” He returned home in 1857 following his mother’s death. In 1862, he was invited to evaluate provincial exam papers in Dingxiang County but succumbed to liver disease on December 9 the same year, aged 40.

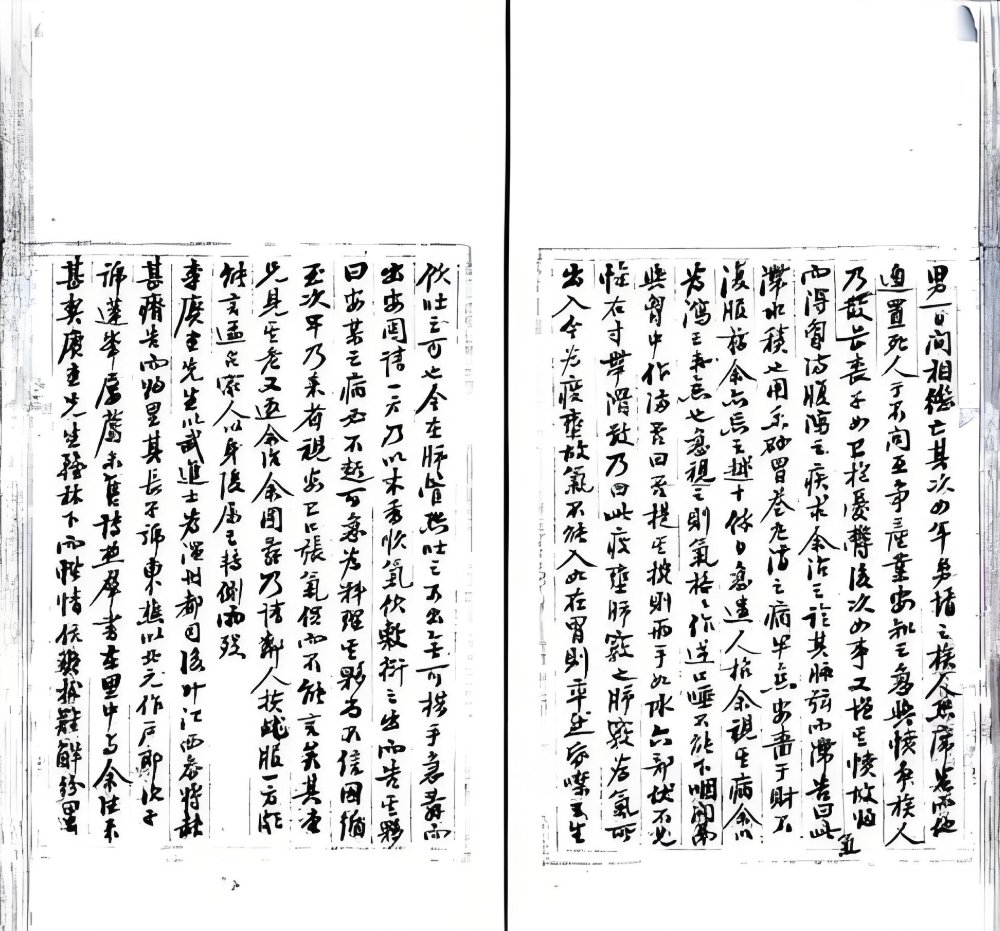

Though not a professional physician, Wang approached medicine with rigor. His famous analogy states: “Prescribing medicine is akin to commanding an army; pulse diagnosis resembles adjudicating legal cases.” For each case, he meticulously researched medical texts, innovatively blending classical methods to achieve remarkable cures.

(III) Medical Ethics and Achievements

A poignant anecdote illustrates his integrity: When a cured peasant’s wife, Mrs. Duan, offered wine and meat in gratitude, Wang refused, knowing her family’s poverty. He treated nobles and commoners alike, always declining gifts from ordinary folk.

He actively documented folk remedies, including:

A Zhao County eye doctor’s acupuncture (supports) for cataracts

A Xibao Village monk’s use of raw tofu to treat leg ulcers

These were recorded in his medical texts. He also researched the local herb Mianshan Xuejianchou ( “Blood-Sees-Grief Herb” from Mount Mian), expanding traditional pharmacopeia.

(IV) Major Work

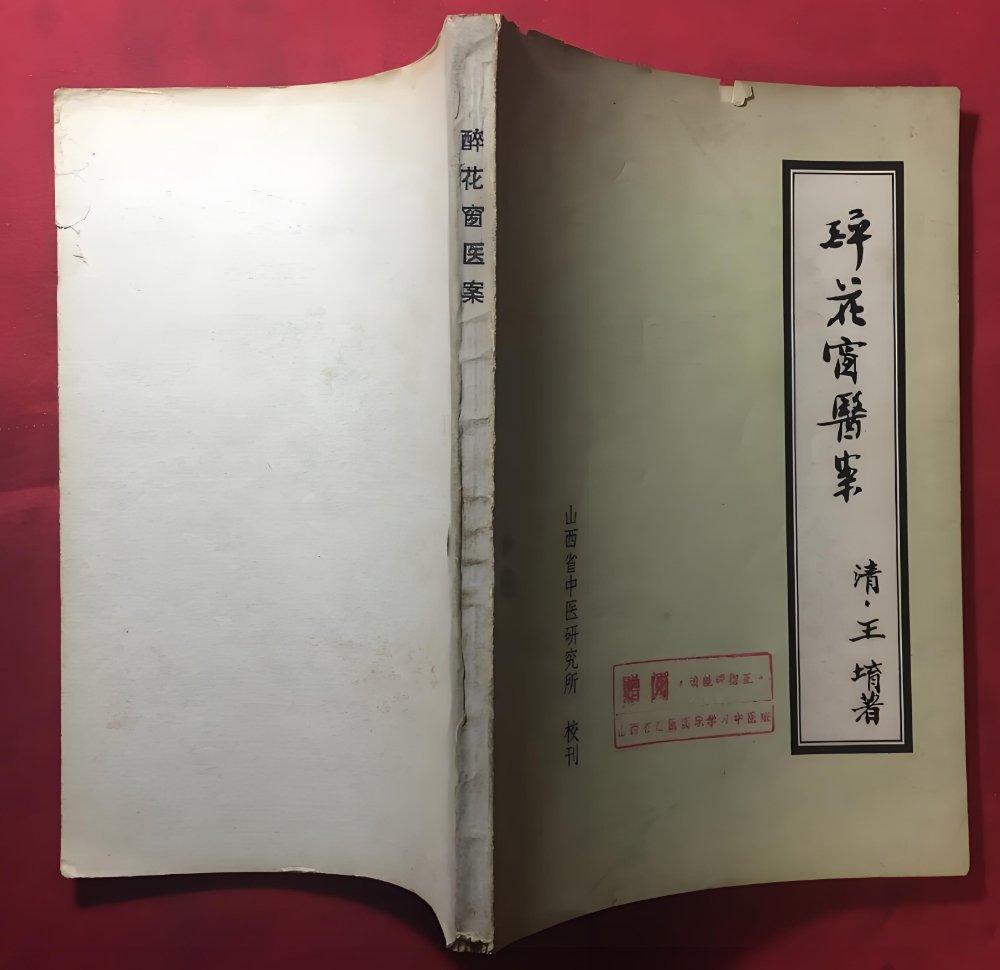

In later years, he compiled his clinical experiences into Mai’an (Pulse Records), also known as Yi’an ( Medical Cases), documenting over 100 cross-disciplinary cases with detailed patient histories, symptoms, and treatments. The manuscript was lost for decades until the 1960s, when Professor Zhang Zhongge of Beijing Agricultural University rediscovered it at a recycling station. Published in 1979 as Zui Hua Chuang Medical Cases ( Medical Cases from the “Drunken Flower Window” Study), it gained widespread acclaim.

(V) Multifaceted Talents

Beyond medicine, Wang was a poet, calligrapher, and linguist:

Critiqued social ills through verse, notably Yangyan Bayong ( Eight Odes to Foreign Opium) exposing opium’s harms

Mastered Manchu and classical texts

Excelled in calligraphy, practicing daily for leisure

His medical writings also chronicle friendships with poet Qi Junzao and female poet He Xingyun, alongside capital city anecdotes and performer lore, earning comparisons to the Song-era Dongjing Menghua Lu ( Dreams of Splendor in the Eastern Capital).

(VI) Historical Legacy

Wang inherited the erudite tradition of Eastern Han scholar Guo Tai ( a fellow Jiexiu native), embodying polymathic brilliance:

Stately stature with piercing gaze

Charismatic personality and talent for mentorship

Expertise in astronomy and calendrics

Modern experts hail him as “Shanxi’s medical pinnacle,” recognizing his dual mastery of medicine and humanities. His case records remain vital for studying Qing-era medicine, exemplifying the synergy of traditional Chinese medical theory and practice.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We\'ll assume you\'re ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Read More

Leave a Reply